Delta Airlines recently experienced what it called a power outage in its home base of Atlanta, Georgia, causing all the company’s computers to go offline — all of them. This seemingly minor hiccup managed to single-handedly ground all Delta planes for six hours, stranding passengers for even longer, as Delta scrambled to reshuffle passengers after the Monday debacle.

Where Delta blamed its catastrophic systems-wide computer failure vaguely on a loss of power, Georgia Power, their power provider, placed the ball squarely in Delta’s court, saying that “other Georgia Power customers were not affected”, and that they had staff on site to assist Delta.

Whether it was a true power outage, or an outage unique to Delta is fairly insignificant. The incident was a single company without power for six measly hours, yet it wreaked much havoc. Which brings to mind (or at least it should) what happens when the lights really go out — everywhere? And just how dependent is the U.S. on single-source power?

When you hear about the possible insufficiency, unreliability, or lack of resiliency of the U.S. power grid, your mind might naturally move toward the extreme, perhaps National Geographic’s Doomsday Preppers. Talks about what a U.S. power grid failure could really mean are also often likened to survivalist blogs that speak of building faraday cages and hoarding food, or possibly some riveting blockbuster movie about a well-intentioned government-sponsored genetically altered mosquito that leads to some zombie apocalypse.

But in the event of a power grid failure—and we have more than our fair share here in the U.S.—your survivalist savvy may be all for naught.

This horror story doesn’t need zombies or genetically altered mosquitos in order to be scary. Using data from the United States Department of Energy, the International Business Times reported in 2014 that the United States suffers more blackouts than any other developed country in the world.

Unfortunately, not much has been done since then to alleviate the system’s critical vulnerabilities.

In theory, we all understand the wisdom about not putting all our eggs in one basket, as the old-adage goes. Yet the U.S. has done just that with our U.S. power grid. Sadly, this infrastructure is failing, and compared to many other countries, the U.S. is sauntering slowly behind many other more conscientious countries, seemingly unconcerned with its poor showing.

The Grid, by Geography and Geopolitics

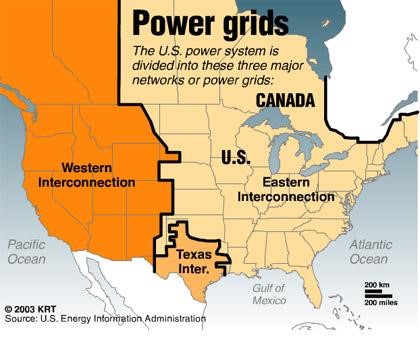

According to the United States Department of Energy, the American power grid is made up of three smaller grids, known as interconnections, which transport energy all over the country. The Eastern Interconnection provides electricity to states to the east of the Rocky Mountains, while the Western interconnection serves the Rocky Mountain states and those that border the Pacific Ocean.

The Texas Interconnected System is the smallest grid in the nation, and serves most of Texas, although small portions of the Lone Star state benefit from the other two grids.

And if you’re wondering why Texas gets a grid of its own, according to the Texas Tribune they have their own grid “to avoid dealing with the feds.” Now that’s true survivalist savvy—in theory.

When you look at the layout of the grid above, it’s easy to see that a single grid going offline would disrupt a huge segment of North America.

Wait—make that all of North America.

To give it to you straight, our national electrical grid works as an interdependent network. This means that the failure of any one part would trigger the borrowing of energy from other areas. Whichever grid attempts to carry the extra load would likely be overtaxed, as the grid is already taxed to near max levels during peak hot or cold seasons.

The aftermath of a single grid going down could leave millions of residents without power for days, weeks or longer depending on the scope of the failure.

So although on the surface it looks like the U.S. has wisely put its eggs into three separate baskets for safer keeping, the U.S. has in essence, lined up our baskets so that if one were to drop, or if the bottom were to fall out, the eggs from basket #1 would fall into basket #2. Which would break from the load, falling into basket #3—eventually scrambling all the eggs. Sorry, Texas.

When multiple parts of the grid fail at the same time, it’s not necessarily more catastrophic—the catastrophe just happens more quickly.

According to Jon Wellinghoff, chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, in an interview with USA Today, “You have a very vulnerable system that will continue to be vulnerable until we figure out a way to break it out into more distributed systems.”

The Grid, by the Numbers

Let’s look at the math behind the power grid, and what the U.S. is doing to improve it.

1. Through the Recovery Act, the DOE invested about $4.5 billion in the power grid since 2010 to modernize it and “increase its reliability”. $4.5 billion seems like a fairly large number, unless you’re talking about a single machine that serves as the lifeblood to nearly every human in North America—a machine that was conceived in 1882 by Thomas Edison—with little changed since then, conceptually speaking. For people who reside in weather-challenged areas, such as my home state of Michigan, a home generator is almost as necessary of an appliance as a microwave, and people are scrambling to go “off-grid” with alternative energy solutions—an act that will not provide them immunity should the lights go out everywhere else. And for what it’s worth, for those of you sporting solar and wind energy, you’re further taxing the grid—the grid just wasn’t designed to accommodate the surges and lulls of such systems, however green you find them.

2. Power outages—just the ones due to severe weather—cost the U.S. economy between $18 and $33 billion annually in spoiled inventory, delayed production, grid damage, lost wages and output. Despite a few billion dollars being thrown at the grid to improve its resiliency or reliability, the number of outages due to weather is expected to increase, assuming that climate change will indeed intensify extreme weather, as some predict.

3. The total annual cost from power outages, per federal data published in The Smart Grid: An Introduction, is a whopping $150 billion.

4. As of 2014, the DOE had generously spent $100 million (million, not billion) into modernizing the grid for the specific purposes of surviving a cyber incident by maintaining critical functions. This would be measures separate from making the grid more reliable.

5. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave the electrical grid a grade of D+ in early 2014 after evaluating the grid for security and other vulnerabilities.

6. The average age of large power transformers (LPTs) in the US is 40 years, with 70 percent of all large power transformers being 25 years or older. According to the DOE, “aging power transformers are subject to increased risk of failure.”

7. LPTs cannot be easily replaced. They are custom built, have long lead times (even 20 months, in some cases), cost millions of dollars, are usually purchased from foreign entities due to limited U.S. capacity, and weigh up to 400 tons. All this means that patching and fixing is likely to be favored over replacement, despite their age and associated risk.

Working with those figures, most of which are provided by federal sources, this means the U.S. invested, from 2010 to 2014, $4.5 billion to modernize the grid, along with an additional $100 million to stave off cyber threats. That’s $4.6 billion over four years, or $1.15 billion per year in upgrades. Next to the $150 billion lost each year due to outages, it looks like someone has done some subpar calculating.

The security of the power grid, which is a separate issue from the reliability of the power grid, is a whole other issue that concerns itself with hypothetical one-off scenarios—albeit terrible one-off scenarios. But at least there’s a chance that those one-off scenarios, such as a cyber-attack on the grid or some terrorist activity, would not come to fruition. A chance, at least.

What we are certain of, is that severe weather will continue to stress and threaten our power grid. And unless something changes, ultimately, it will fail. So when we talk about reliability, we’re talking about “when” and “for how long” scenarios, not “what if”.

The how-long factor plays a huge role into how bad is “bad”; not because of the events that one knows will follow, which includes mass food spoilage, deaths due to overheating in the hot summer months, deaths due to freezing in the cold regions, and the halting of everything we take for granted these days—airlines, internet and most other forms of communication.

All that sounds pretty bleak, but when you throw into the mix the mania and hysteria that would ensue shortly after such catastrophic events, it will be so much worse. Best-selling author Charles Mackay, in his book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, does a pretty good job describing, through example, how crowd decisions and reactions are significantly less sensible than individual decisions—sometimes downright nutty, as evidenced by Tulip Mania, where supply and demand—or in this case scarcity and demand, drove up the prices of tulip bulbs to ridiculous levels.

In the context of blackouts, we saw this in 1977, when a lightning strike in New York on a Hudson River substation tripped two circuit breakers, causing power to be diverted in order to protect the circuit. The chain of events that followed ended in an entire blackout for the area, which led to mass rioting, over 1000 deliberately set fires, the looting of 1600 stores, and the eventual arrest of 4,500 perpetrators and the injury of 550 officers, according to some estimates. The power was only out for 25 hours, and in one area.

In all likelihood, the haves (those who have removed themselves from the grid and prepared accordingly) will soon be overrun by the have-nots in the event of any extended blackout, with heavily populated areas taking the brunt of the chaos—and your solar roof panels or generator will not suffice as your savior.

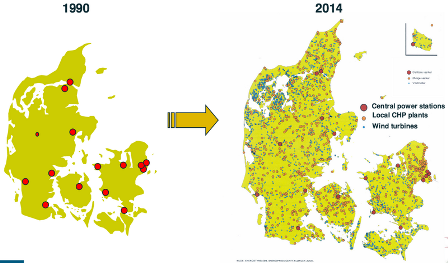

The U.S. would be wise to follow the lead of some other countries, such as Denmark, which has decentralized its grid, but we doubt the cash exists to fund such an ambitious overhaul of an archaic system that has been left essentially unattended for decades upon decades.

by Newsroom