Once we join this prepper culture, we start getting pushed toward heirloom seed stockpiles. There’s definitely value in heirloom and open pollinated. There’s also a reason we developed hybrids.

They have some big benefits, see, especially for preppers in crunch time. There’s some considerations that can help us decide when those benefits outweigh heirlooms/OPs, when true-seed options are better, and when it really just doesn’t matter which we choose.

*Also consider foreign domestic crops and wild edibles for challenging conditions. This is “don’t hate on hybrids – they’re wicked helpful” not “hybrids are the one and only way”.

Quickie Snippets

One – The defining characteristic of heirloom/OP’s is that we can harvest their seed, replant it, and reliably get the exact same plant all over again. (OP’s are basically a younger version of heirlooms; like having a 1980’s pickup versus a 1920’s pickup.) Not so of hybrids – second-generation hybrids are a crap shoot.

Two – Not all hybrids are GMO. A hybrid is just a crossbreed – a labradoodle specifically created from a Labrador and a poodle. We were breeding hybrid plants long before we had the ability to genetically modify organisms for mass production and planting.

Before anybody goes there: Yes, breeding is genetic modification, but only by the loosest of definitions. By the same looseness of definition, chalk is Information Technology. However, we recognize IT as computer based. So… No, breeding isn’t genetic modification. Breeding is genetic selection – determined/intentional or artificial selection in this case, versus natural selection.

Three – “Hybrid” has NOTHING to do with growing methods. (Organic seed sourcing isn’t worth getting worked up over as health issue, either.)

Hybrid Vigor

There’s a handful of the challenge solutions behind the creation of most hybrid crops that particularly apply to us as survival growers.

– Determinate yielding – produce consistent, uniform harvests within a fairly small time window (There are pro-con’s to weigh with indeterminate and determinate options – neither is always better.)

– Climate Resistance – produce despite drought, heat, cold, wet soil, and humidity

– Soil Resilience – produce across wider soil types and less-fertile soils

– Pest & Disease Resistance – creating immunities, reducing symptoms of disease, and making crops less-attractive to various pests

– Speed – bears harvest faster (Can be eliminating daylight-cued needs or streamlining plant form.)

– Higher Yields – produce bigger fruits or more fruits, or both

– Compact Forms – production at smaller sizes (Usually it’s to grow more in an area/volume or to eliminate the growing time a plant needs to reach the larger size, which shortens the season and allows that plant to be grown in more areas; sometimes it’s for easier maintenance and harvest or increased market, like specialty container veggies.)

There are heirlooms and OP’s that have been tailored for decades and centuries to certain climates, retaining or gaining resistance to diseases and resilience to conditions. Especially for raw-churned land, beginners, humid areas, preexisting-disease areas, and tight spaces, hybrids are typically higher-yielding plants.

*Again: Remember those foreign domestic crops and wild edibles. Don’t miss out on the benefits of hybrids, but they’re just one of many tools on our belts.

Mitigate Losses

Hybrids with quick turnaround can be lifesavers in avoiding the worst of summer’s heat and drought, and getting a crop in and harvested after a seed or plant loss from animals, waste or chemical contamination, floods, and early or late frosts. That limited time also applies to situations where we’re bucking out lawn by hand at the beginning of a season, with part or most of that season gone by the time we’re able to plant.

Hybrids are also big if we find ourselves trying to plant with limited season left because we evac’ed somewhere or were delayed by an injury.

Likewise, fast-moving Big Things (Cuba-like shortages, asteroid/volcano dust blocking heat/light or clogging preexisting crops, & “I’m done with lettuce being more dangerous than public roads” outbreaks) can make fast-turn crops enormously beneficial.

Yeah, there are heirloom fast crops. Especially when we need the most out of gardens, and especially when we’re time crunched, those differences of 5-15 days and 20-35 days can mean the difference between salad greens and squash, wheat and hay/silage, blanks on corn stalks or tiny baby ears – and, roasting ears or dry ears for storage.

If a hybrid can get an already-fast crop to plate, jar, and cellar even faster … why would we ignore that potential, especially for hard times?

Hybrids can be huge if we end up with a soil-borne or insect-vector disease, insect pests, or nutrient deficiencies. We have to make sure we’re getting that type of hybrid – it’s not universal – but they’re out there, especially for the crops that are most susceptible to things like the mosaic viruses, to the bacterial and fungal diseases that so commonly pass between fruit trees to our beans and tomatoes and berries or from infected lawns to our barley, and to the critters that like to munch a certain crop and either decimate the crop directly or transfer a disease that decimates them.

Seed Saving

This is the basis for a lot of arguments, but we don’t always need a breeds-true seed. We don’t need the seed-saving capability from things like sprouts we’re eating way before it would mature, and in some cases, the one-off root and leaf veggies that we’re following with other crops way before they could mature enough for seed. Go with the least-expensive and most-reliable option.

The biggest factors in deciding when we do want heirlooms, even if they’re more expensive or less productive, involve how long the plant is growing before it’s consumed (sprouts, microgreens, radish, beets, corn, green beans) weighed against how long it takes to produce seed (biennial carrot, turnips, mustard – 21-60 days to harvest lettuce, 70-100 days to seed; 65-90 days for sweet corn, 95-120 to collect seed).

How many seeds we need to plant each year (tomatoes, summer squash; lettuce, carrot) is also a big influence. We also want to consider how much seed each particular plant produces (peas, vs. broccoli, vs. melon) and how easy/difficult it is to collect viable seed (biennials, tomatoes, spinach vs. beans, melon).

From those, we can determine if we’re able to provide the care plants need to reach seed-bearing maturity, which can involve a full two-year cycle or fermenting, and enough space for enough plants to replace seed.

That tells us if we can feasibly collect our own seed or if the primary reason for going with an heirloom/OP just went out the window.

With the more involved, longer growing, and larger space seed crops, for both people who plant pounds per crop and people who aren’t even planting whole packets at a time, it usually balances to get whatever’s most efficient and least expensive, regardless of hybrid-heirloom origin, and stock it deep.

It’s usually the ones in the middle who have both the storage and growing space and the labor/man-hours to make those seed crops worth it.

High-Value OP’s & Heirlooms

Anything that has produced a mature seed at the stage we harvest (dry beans, dry grains and cereals, autumn squash, pumpkins, most peppers and melons) are automatics, even on a small scale.

So are things that only need a couple extra weeks for a mature seed versus the immature “green” seed they carry at harvest (peas, sweet corn, summer squash).

Slightly behind those two sets are the seed crops that are easy, and although time consuming, don’t require that much extra space either to finish growing or in storage – which is enormously relative and situationally dependent.

True-to-seed lettuces and radish can be grown to bolting and seed-maturity stages even indoors. Spinach, too, can provide an early-season green, thinned or transplanted in sets. It’s dioecious, though, so you’ll need both female and male plants to do the job. Indoors, both need hand pollinated.

Outdoors, there’s even greater benefit because the tiny flowers are useful to a number of equally tiny insects that will parasitize some of our biggest pests: slugs, caterpillars, and squash bugs and their similar-shaped cousins.

High-Value Hybrids

First, repeat the heirloom/OP list. This time, it’s for the ability to get container-garden and hanging-basket options, faster production, and the disease, pest, and weather resistant cultivars.

The same reasons apply to getting short-season and container-friendly corn hybrids, and pest-resistant and less-nutrient-greedy grains.

Likewise, turnip and beet hybrids that can be harvested in 35-50 and -65 day ranges, and carrots that perform in those periods can help us hugely, especially if we have hot summers and not much “buffer” season for those cool crops in spring and autumn. The speed also helps us turn a crop as pantries run bare, and clear an early fast crop if we have short summers to take advantage of.

Best of Both Worlds

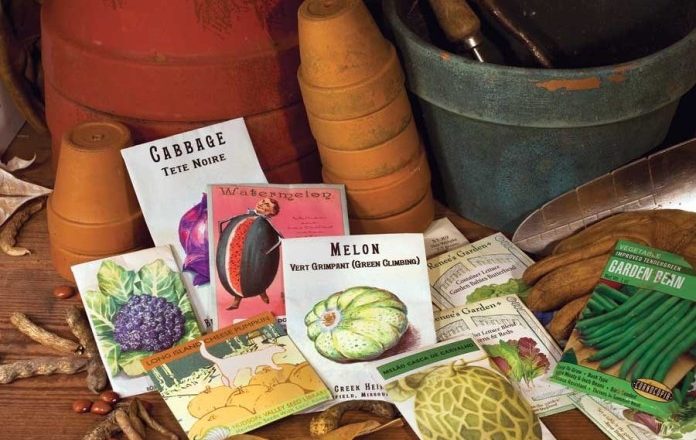

Ideally, we have both general categories of seed in our storage – OP’s (open pollinated)/heirlooms that breed true and hybrids with their one-off but powerhouse strengths. Even more ideally, we’ll have both categories for all of our crops, although that’s not always realistic.

Don’t let fear mongering, fear sales advertising, or what “everybody” does drive you. Actually weigh out what’s better – for each of us, as individuals in a whole range of climates and situations, condo or flat to ‘burbs to woods lots, with different draws on our time and different skill levels.

Mostly, when it comes to seeds, pick the least-expensive option that matches our skills, uses, the space and season length we have to work with, and our soil.

*One last time: “Don’t hate on hybrids – they’re wicked helpful” does not mean “exclude other helpful things”. We have whole worlds of food production and foraging to improve our yields.

by R.Ann Parris