Tis the season of garden harvests in North America (and garden planning south of the equator). If we’re lucky, it gets to the point where we look at the harvests accumulating in our freebie buckets and hoarded supermarket bags and remind ourselves that abundance/overabundance is a good problem to have.

There’s probably 101 ways to preserve our harvests. I’ve written articles in the past focusing on some of the less “usual” methods.

Others at TPJ have covered preservation methods as well. This time around, I’m going to touch on some prepper-specific aspects of today’s standbys: canning and dehydrating.

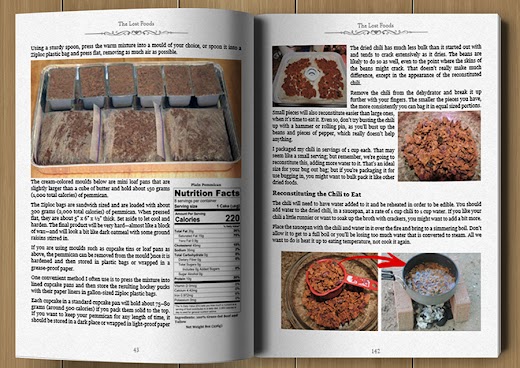

Quickie Snippet: Leave some produce whole and halved when possible. Bigger pieces increase our options for later. That variety and having some fork-and-knife or finger-food options will be even more important in a crisis.

Canning Quickfire

The information is out there and the old hats know it by heart. Just to recap and intro beginners…

Pressure Cookers are not pressure canners. (Unless it’s one of the new ones that specifically says it’s both a cooker and a canner.)

Electric stoves go through a cycle of heating, “coasting”, and reheating. They’re iffy for canning. I love my glass-top, but we either go to Mom’s (netting Pops’s knife-giddiness for help chopping and Mom’s enjoyment of this activity is incidental, honest) or I use a wood-stove or bust out the mini propane cook top.

– WBC/Steam Canning is water-bath canning. We use it for high-sugar and high-acid foods.

We do not have to buy a specific canner. Any ol’ pot will work so long as it’s tall enough for a few inches above our canning jars after we stick some butter knives, jar rims, or dish towels in the bottom.

(Don’t stick jars directly against the bottom of pots. It creates weakness in the joint at the bottom of the jar. The next time we process those jars, we’ll likely start getting breakages.)

The any-pot option becomes big, because, One, yay, less spending, more multi-purposing. Two, yay, no excuse not to get started today.

Three, easy-peasy tailoring. If I’m doing tiny pickled onion or itty-bitty special-treat jars, I can use a wider, shallower pot (and not have the shimmy-shake stack ‘em issues) or a small saucepan. For big ol’ quarts, I just grab a taller pot.

Tidbit Time: Make finger-food or forkable sweets. Any jelly can turn into candies or Jello-Jiggler-type treats. Follow the instructions for firm cranberry sauce or let your recipe go 1.5-2x the time it takes to get to a sheeting gel stage. Use no-neck jelly jars; they’re easier to get it out for slicing (then, cookie cutters!).

Reuseable Lids sometimes have iffy anecdotal reviews or restrictions about pressure canners, and we’re still going to want to have extras for breakage. If you get the type that rely on rubber rings, those rings will eventually warp, pit, and dry rot, so, snag extra-extras.

PC/Pressure Canning is done with a pressure canner. (Not a pressure cooker.) We use it for low-acid foods. Super-big bonus: It lets us can any foods without the usual inputs.

Just follow carrot, potato, meat, or soup recommendations. No pectin, pickling salt, vinegar, or sugar. None of the salts or fats needed for cured meat.

Plus, it typically burns less fuel than smoking foods.

Pick PC’s Carefully

Some pressure canners have rubber gaskets that can become brittle and pitted. From the prepper perspective, something that needs replacement parts requires extra attention (and space, $$$). Some brands already have hit-and-miss parts availability.

Serious suckage goes into effect when there’s produce piled up and a ring looks bad. It’s worse when it’s fish or meat in jars and the canner isn’t holding pressure because a seal is leaking.

Compare steel-on-steel options with parts that can sit somewhere for an eon if long-term reliability is a priority.

PC v. WBC

PC’ing takes a lot of time. There’s not only the 20-90 minutes it takes to actually process, but also the time a canner is coming up to pressure and then the time it takes to bleed off that pressure. A single canner load can take hours.

The immediate takeaway there is: Get the biggest pressure canner you can afford, so you can do as much as possible per load.

Especially preppers looking at power-outage reasons for canning, when budgeting for canners, consider how much you can afford to let sit out (in what season) while loads process. Don’t forget to account for the freezer and game/livestock.

Upside, with pressure canning you need to keep an eye on things, but you can be processing other produce, playing cards, brushing dogs…

With WBC, things happen fast.

One, you’re working fast – before things cool off. Two, the times are shorter, 5-15 minutes, sometimes 20-30 because of altitude. In the time it takes to run one PC load, you can have 2-5 WBC loads done (even when it takes a disproportionate time for jam to return to a boil).

WBC is regularly a little hectic for me. Others actually enjoy it. Having multiple people is definitely a bonus. (I think the people who WBC jam and jelly by themselves are possibly magicians … or aliens hiding their extra hands/eyes.)

Hot Tip: Keep some water simmering on the back of the stove while WBC’ing. If you boil off or drip/slosh enough to affect jar coverage, you can top it off without losing heat and time.

Dehydrating

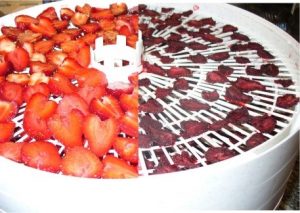

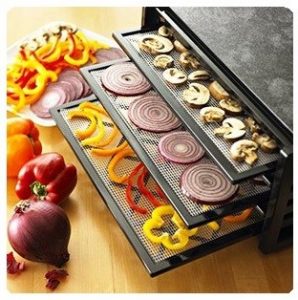

Produce may need a blanch or we may need to pre-cook some foods, some things do best grated, and some things take eons, but we can dehydrate pretty much any produce (frozen as well as fresh).

We can do all sorts of medicinal and spicing herbs, wild edibles, and flowers, with little or no damage to their nutrient value. We can even dry greens, although they’re delicate to handle (read: little to tiny flakes).

Make Life Easier: Buy dehydrators with two-piece mesh-and-frame racks, or get some replacements or liners (make your own out of window screen). Flex the screen to get too-thin slices and finicky produce off racks. Easy-peasy.

Dehydrating has huge benefits from the simplicity alone. Slice, spread out, hang/slide racks, and then, we just walk away. Crazy, yo.

Sure, keep an eye out, but this is going to take 6-20+ hours by method and produce. At most we’re flipping things for uniform airflow once or twice in there.

Dehydrating is an enormous space and weight saver. Foods reduce by at least half, and commonly reduce to a quarter or fifth the weight and space. (Warn people that there are 3-5 bananas in that half-pint jar).

Be Thrifty: Save canning jars for canning. Keep condiment and sauce jars for dehydrated produce. We can use oxygen absorbers to vacuum-seal their lids, too. Same “pinnng” pop-down.

Drying foods requires no outside resources once you have the screens/racks, as opposed to canning, which is going to require at least replacement lids.

Purchasing an electric dehydrator isn’t always necessary (though, they have their benefits). Air or sun drying foods is still getting done with meats, fish, and produce all around the world. I’m all about a cover or screen to keep pests off, personally, but it’s not always necessary.

I’m also in a high-humidity location. I must have either low-draw plug-in fans or battery-operated fans that run off rechargeables to air dry, and thus a small power source to handle my fans or charge those batteries.

Weather Versatility: Too humid, buggy, or rainy for open-air drying? Cold smoking (not your average smoker or grill; they’re too hot) shares some of the same benefits.

Harvest Size

Along with our hardware, the size of incoming harvests can play a major role in deciding what methods we use for that preservation, especially if we’re conserving power or in a total outage.

Right now when we don’t have a ton of something, but won’t eat it fast enough, or we want to store limited-season harvests, we can toss it in the freezer with at most a blanch. When we have enough to justify running a dehydrator/fan or canning (or enough time) we pull it out, maybe defrost and drain it, and off we go.

Later, a fridge-freezer may not be available.

Even if we arrange our planting for staggered harvests and increase focus on storage-friendly field-to-shelf crops, we’ll still (fingers crossed, knock on wood) have things we want to preserve.

Factoid: Loads do not have to be all one thing, but don’t dehydrate onions with your chamomile, stevia, or fruits in small spaces (oniony-peaches, eek!). When mixing loads in PC’s, similar pressures and times work best – we’re using the highest-longest – but also think canning stew, just with ingredients in separate jars. (Expect texture loss for plums and carrots processed with potatoes and chicken.)

WBC’ing commonly requires some pretty balanced ratios. Jellies and jams especially are finicky about doubling or halving recipes. Pretty much anything can be pickled, meat to melon, though, which leaves some options.

A PC’r will stand up for a lot of our freezer uses. It has that time-suck factor, as well as drawing on some sort of fuel, but it’ll also be a way to safely store leftovers for later.

Grid-Down Preservation

We have lots of options for preserving foods, but as preppers – especially if we have limited power sources and-or a mind toward self-sufficiency – we have some considerations the average gardener and canner doesn’t worry over.

The inputs preservation requires are one key aspect, whether it’s energy sources, lids and jars, or actual ingredients. Time, involvement and versatility are others.

All canning requires a governable, steady heat source – especially PC’rs that need to stay at pressure for 20-90+ minutes – so it’s pretty critical that we do some practice with our power-outage cooking methods.

We’ll want to figure out how much fuel we need for preservation, and tinker on woodstoves, campfires, and charcoal grills, especially, learning to control and maintain constant heat.

As with producing foods to preserve, jump in and get started, using as many methods as possible. It’s a leg up on hard times, personal or widespread, even “just” preventing grocery losses during an extended power outage.

source :R. Ann Paris