Some of us are restricted entirely to small spaces, and some of us have either clay, rock, or sandy soils that are easier to avoid than to mitigate. Some of us keep container gardens going for convenience, enjoyment, and mitigating seasonal threats from pests to cold, high winds or thunderstorms to dry conditions, even when we have some elbow room and decent starting soil.

On a windowsill or a bookcase, up on a balcony or down on a patio, and even out in the yard or lining our driveway, there are some practices that can make our container gardens more productive, more efficient, and easier to maintain.

Mulch Containers

Even small containers can benefit from mulching. Indoors or out, it limits evaporation, and it prevents compaction from overhead watering and rain.

It also reduces the number of weeds with immediate access to soil for outdoor containers, both decreasing competition with plants we want and making them easier to pull and with less disturbance to our plants and the soil.

Mulching also has significant value in providing an insulating barrier. That insulation protects tender seedlings just starting roots from drying out, and can help mitigate both heat and cold.

That’s particularly valuable when it comes to containers, because they’re prone to drying out and vulnerable to weather extremes.

Go Big

We’re talking container size here, not leaping whole hog into a massive investment of time, energy, and resources by lining every possible vertical and horizontal inch with plants.

Even when provided with nutrient-rich soils and liquid feeds, plants do better with some room to groove. In the ground or larger beds, roots are able to spread readily. Smaller containers limit not only the depth, but also the width roots can expand into.

(The really tiny tabletop strawberry planters are notorious for problems due to overcrowded roots.)

The relationship between square- and cubic footage, total volume and surface area, all factor in when it comes to planters and beds.

The ability to access additional root space and water from the soil under each successive tier is what makes some types of herb spirals, stair-step planters, and pyramids so successful and efficient when square footage is limited.

We can get away with a little bit more for short-lifespan plants that are being harvested as baby leaves, but for perennials and larger plants, adequate root space greatly impacts success over the season.

When eyeballing planters, don’t forget to decrease the usable space by about an inch at the top – soil will settle, but containers that are filled right to the rim will overflow quickly and we’re likely to lose soil as we dig in there.

Pot Mods

When selecting a container, evaluate it on not just the soil volume and dimensions, but also the ability to add additional drainage holes.

Ideally, we’ll be able to put in those extra holes 1-4” up the sides of the pots, providing both adequate drainage that many pots lack, but also the ability to do a fill with rock, sand, mulch, flake animal bedding, pine cones, branches, or empty soda bottles peppered with holes.

The junk-filled space creates a reservoir area that limits how often we need to water, much akin to sub-irrigated planters and still-water hydroponics/aquaponics methods.

While we’re at it, we might also consider adding a PVC tube, soda bottle with holes drilled, small clay pots epoxied together, a small transplant pot buried to ground level, or similar to create ollas or a chute that will help us deliver water directly to the root zones.

Doing so limits evaporation loss, some pests, and can make watering faster – we can dump and go, rather than slowly soak.

Watering & Washout

Water creates two of the biggest challenges to both raised beds and container gardens. Material selection can factor in, increasing evaporation like clay pots – which isn’t always a bad thing – or exasperating heat issues like many metal and dark containers – which, again, has benefits in some seasons and climates.

The greatest factor is usually just the soil-to-plant ratio. There’s just not much water-holding capacity in many planters.

That means we’ll typically have to water more often, versus plants that are in bigger beds or the ground.

In addition to creating reservoirs for our plants, if we can, try sinking containers in the ground – even partway. It can provide not only additional access to water and decreased water drainage, but also some temperature regulation.

Nutrients washing out of pots during heavy rains is also a common issue.

It can be combated by using plastic or poly covers, or by adding fertilizers in small increments to the top of planters, rather than mixed into the soils, whether that’s coffee grounds and Epsom salts sprinkled on top, feeder sticks, in-situ composting, or liquid fertilizers applied as we water.

Add Amendments

No matter how we combat things like irrigation needs and washout – or if they’re even factors that affect our containers – we have to revitalize the soil in our planters, just like in beds and in-ground plots.

Some containers are large enough for compost chutes/tubes or even “trench” composting methods.

Intensive Spacing

We can absolutely use individual planters to mimic the tight spacing we see in intensive gardening methods like square foot gardening and bio-intensive or bio-dynamic gardening.

Buckets, troughs with at least six-inch soil depths, and similar shapes make conversions easy and simple and can maximize the typically square worlds we inhabit. Storage totes and lined or plastic drawers share similar benefits, but even smaller containers like cut-down soda bottles can work.

However, it requires the same super-rich soil mixes we’d use in beds.

That means additional amendments and the ability to re-mix soils, which we need to plan for in our spaces.

Be Ruthless

While we can congestion plant our containers, we do have to give plants the space they need. Many gardeners both large and micro scale are prone to overcrowd or skip thinning, for a variety of reasons, to the detriment of their yields.

Finding the happy medium between wasted space and bare soil, and overcrowding plants – stunting them as they fight for root space, sunlight and nutrients – requires a little practice. Our exact soil mixes, feeding, irrigation, and the humidity, wind, and heat of our environments affect the exact spacing.

Ruthlessly selecting our “keepers” can start even earlier, particularly if all we have are small-space containers. We have to be realistic about not only what will grow – productively – in that space, but how many plants it takes to harvest usable amounts at a time.

While there is value in any growing – both mentally and the practice it provides – planning worthwhile plantings will help us better assess in the long run.

When we’re restricted, we might skip the large, long-growing plants that may offer only 1-2 harvests, such as ball cabbage, broccoli, corn, or some large winter melons.

Instead, we might focus on the indeterminate, cut-and-come-again, and staggered crops that give higher total yields at faster rates, such as smaller summer or acorn squash, lettuces, peas that offer greens as well as pods, and cherry or grape tomatoes.

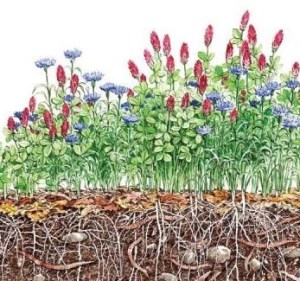

Cover Crop

Container gardens benefit from cover crops just like raised beds and large plots. The fumigant, disease-cycle breaks, revitalization, soil loosening, aeration, and drainage benefits all apply even at micro-scale.

To get the most out of a container cover – especially with limited space – aim for those that also offer culinary or medicinal uses, or will provide small-animal feed or mulch for our planters.

Some can also provide early- and late-season flowering for beneficial insects, birds, and bats that are as useful on skyrise balconies as they are for rural gardens and orchards.

Companion Plant

In some cases, like inter-planting onions and lettuce, companions are possible even in small containers.

Other times, like keeping marigolds or basil near tomatoes instead of sharing a tote, we might not get the full benefits companion planting can produce, but their presence still offers some assistance.

Flowering culinary herbs, nasturtium, echinacea, and flowering wild edibles can commonly do double duty.

They aid pollinators early, late, and during flowering gulfs, encourage the predatory and parasitic insects that lower our pest loads, serve as camouflage and “bug breaks” between our edible crops, and help repel human-munching bugs and crop pests, while also providing a direct harvest for spicing, medicinals, or greens.

Cluster Containers

Interspersing our veggies nets more than the benefits of essentially companion planting.

Keeping planters together instead of spread out can help shade the containers and any bare soil in summer, reducing heat and evaporative losses that lead to extra irrigation.

It also provides a larger mass, which aids in temperature regulation in both summer and on the cooler fringes of spring and autumn.

Ready, Set, Grow

Container gardening fits into almost any lifestyle. Whether we’re restricted to a windowsill or a shelf with a lamp, or have acres to play with, there are numerous benefits to adding some pots or trays to our production.

The local garden club or Master Gardener association and sometimes even our ag extensions can offer additional suggestions for improving yields and making our planters as productive and easy to maintain as possible. So can locals with blogs and YouTube channels, and sites like GrowVeg or seed suppliers.

Wherever we source our information, get started this season. However big or small our production, whatever our motivation for growing, the learning curve is too steep to put it off.

source : R.Ann Paris